JANUARY 1934

“Flying High into '34”

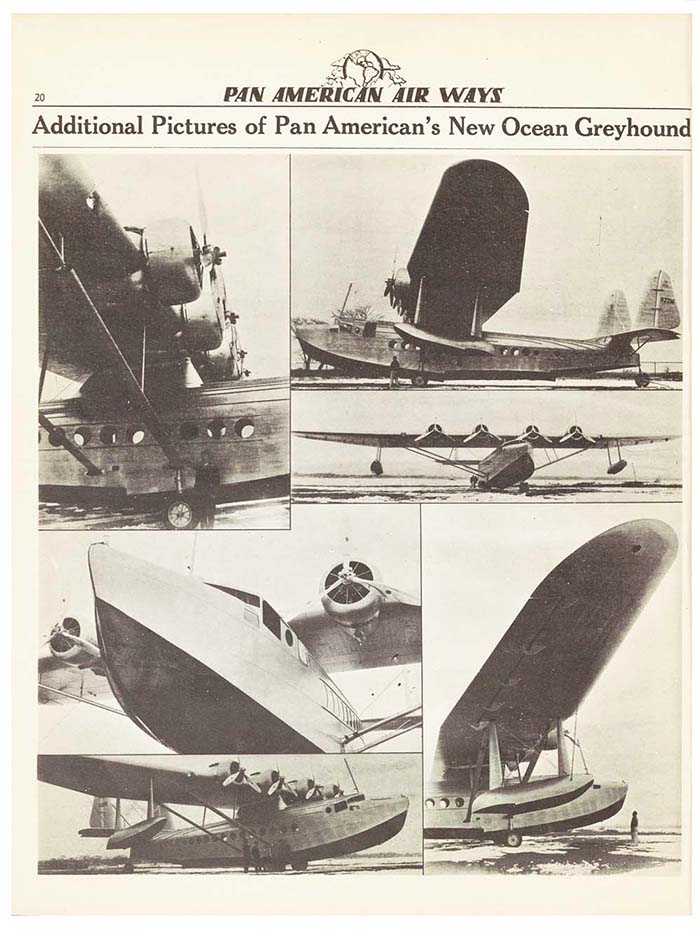

"Pan American's New Ocean Greyhound," the Sikorsky S-42 ("Pan American Air Ways, " Jan. 1934).

Pan American Airways System entered the new year, 1934, having set new performance records for itself the prior year in all but one of the major metrics it shared.

As stated in the January issue of the company newsletter, Pan American Air Ways,

“The following is the operating record of the Pan American Airways System to January 1, 1934.

30,982 Miles of airways in operation.

33 Countries and colonies served.

252,190 Passengers carried.

77,391,757 Passenger miles flown.

12,311,613 Pounds of mail and cargo carried.

94 Ground radio control stations operating.

154 Airliners in operation.

99.678% Regularity of schedule maintained.

2,081 Persons employed.

Aircraft was the sole category with negative growth, and that was good news actually.

Throughout 1933, the company had retired its oldest and least-efficient aircraft and had brought in newer aircraft, most with larger passenger and freight capacity. Company-wide shifting of aircraft moved machinery to routes throughout the Americas to maximize available route load.

And, as aircraft were removed from inventory, President Trippe had been signing multimillion dollar orders for aircraft that would redefine commercial aviation including three Sikorsky S-41s, three Martin M-130s, twelve Lockheed L-10 Electras, and twelve Douglas DC-2s.

Sources:

"Pan American Air Ways," Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan. 1934), p. 12.

R.E.G. Davies. "Pan Am: An Airline and its Aircraft." Orion Books, 1987, p. 33, 37, 39, 44-5.

“A Gift Pays Off”

Size comparison: Top: Historic photo of cargo being loaded on Panagra Ford Tri-motor (Bill Larkins Collection, Wikimedia Commons). Bottom: AI photo of the Andes Mountains.

Pan American-Grace Airways (PANAGRA) Andean Division Manager, John “Johnny” Shannon, read a cable from New York City signed by President J.T. Trippe ordering a flight, Sunday January 14, 1934, along the Eastern Andes following a freak glacier-calving event three days before.

Johnny threaded a Ford 5-AT through the Upsallata Pass to Mendoza, Argentina, picked up the region’s Governor, and surveyed damage along the Tupungato and Mendoza Rivers.

According to New York Times reports, “The station master at Amarillo reported that an avalanche of ice and snow from the glacier dropped into the river at 7 o’clock Thursday evening [Jan. 11, 1934] holding back the river, which was greatly swollen as a result of a day’s heavy rain and the rapid melting of snow during the recent heat wave.” Then, seven hours later, the ice dam broke and “a high wall of water, sweeping along at twelve miles an hour, poured into the Mendoza River, carrying everything before it.”

Johnny reported every bridge on the Transandine Railway gone, swept a half-mile or more downstream by the flood, and railroad beds and roadways washed away. Given construction realities in such remote and rugged conditions, initial estimates suggested that neither rail nor road traffic would return for at least twelve months.

As such, both governments asked PANAGRA to carry all regional domestic mail, in addition to its international airmail allowances, and to increase its freight and passenger capacity for the foreseeable future. So the company shifted its two-day-per-week schedule to daily service, often flying three to four flights to meet demand. This service provided unexpected profits at a time when many Pan Am routes in South America lost money, and the transAndean route never returned to its earlier schedule.

Sources:

“Air Liners Carry All Mail Over Argentine-Chile Mountains.” Pan American Air Ways, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan. 1934), p. 2.

Banning, Gene. Airlines of Pan American Since 1927, Paladwyr Press, 2001, pp. 193-4.

White, John. W. “Argentine Flood is Laid to Ice Jam,” The New York Times, Jan. 14, 1934, p. 6.