THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

Pan Am’s “Super 6”

Rainbow Tourist Class Ad, Pan Am 1952.

Juan Trippe’s Original Vision

If you had to define one critical element of Juan Trippe’s vision for the destiny of the air transport industry, it would be that the value proposition in air travel rested with getting more people onto airplanes.

In his earliest entrepreneurial endeavor, had bought several surplus WWI Navy seaplanes at auction. He was trying to make a go with Long Island Airways – basically an air taxi service to get well-to-do patrons out to the Hamptons as fast as possible. Powered as they were with old, heavy Curtiss OX-5 engines, they could manage just one pilot and one passenger.

But Trippe saw an opportunity. He removed and replaced the Curtiss engines with more powerful Hispano-Suiza engines. Now the airplanes had a 50% boost in lifting power, and he could double his passenger payload to two!

Then, and ever after, airline profits meant passenger loads, or “seat-miles flown” in airline parlance. By the time World War Two had ended, the future of the international airline business meant getting more people to more places in bigger planes with larger capacities.

Pan Am DC-6B Tourist Class Seating Plan.

1945: Trippe’s Great Notion

In 1945 Juan Trippe saw immediate prospects to pursue. Pan Am had acquired dozens of war surplus Douglas DC-4’s which could manage transoceanic routes, and the airline was planning on adding other, more evolved ocean crossing aircraft like Lockheed’s Constellation to the fleet.

Trippe announced that he would slash transatlantic airfares from New York to London to $256. The newly-formed International Air Transport Association (IATA) – of which Pan Am was a charter member – was basically a cartel, formed to keep competition from interfering with normal airline “business as usual.” Other IATA members were dead-set against Trippe’s bold proposition. Their notion of correct pricing was a one-way fare of $375. Their concept was a stable flow of passenger traffic, spread equitably among the various international airlines, with everyone paying the same high price.

In 1945, there was no such thing as “Economy,” “Coach” or “Tourist” class. Civil air travel had been the province of elites. But the world was on the verge of big changes, and Trippe saw that. He knew the way forward for airline profitability was to get more people – many more – into airplanes, and move them to their destinations more quickly so that the aircraft would spend the maximum amount of time moving people. High fares for luxury travel were all well and good (and Pan Am would never stop catering to those who could and would pay more for deluxe air travel.) But future success, he knew, meant a new business model that included getting millions of people into the air, not just a relative handful.

Juan Trippe’s 1945 gambit of slashing transatlantic fares failed, and IATA held the line. The time wasn’t quite right, but fast forward a few years.

Fast Forward, 1952

It’s now the springtime of 1952:

Finally after several years of haggling, IATA’S members have seen the writing on the wall and have relented on the issue of tourist-class fares. On May 1st, all IATA member airlines will be free to offer the much reduced tourist class fare of $486 round-trip from New York to London. The floodgates are about to open on a whole new era of international air travel.

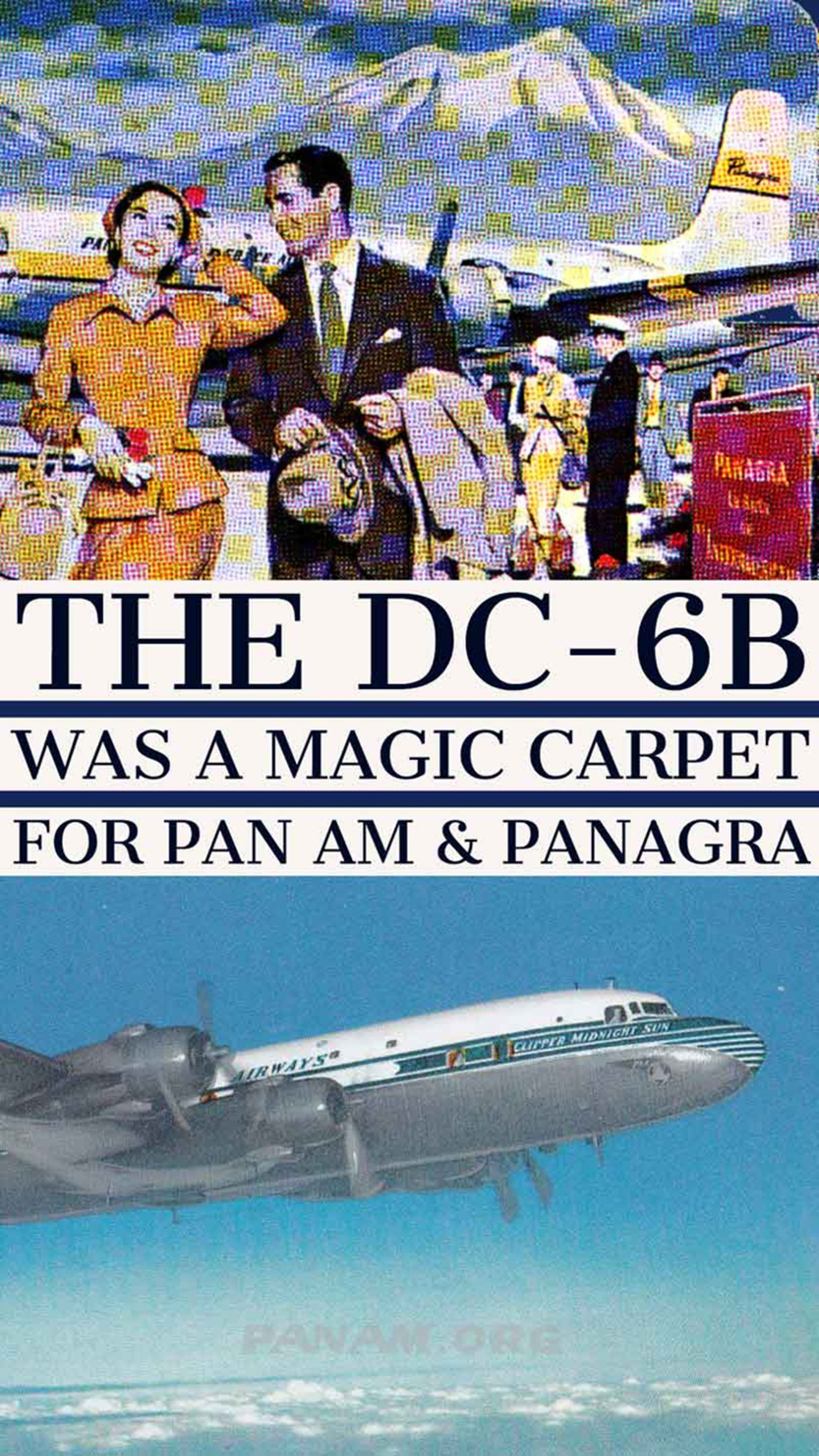

And Pan American will have an edge in the race to operate the most efficient operation – the Douglas DC-6B – a plane whose time had finally arrived. Although the DC-6 first flew in 1946, it had a bit of a rocky development history. In 1944, the US Air Force wanted a pressurized DC-4- like aircraft, and the prototype flew in 1946. But with the war over, the Air Force canceled the order.

Nevertheless, Douglas Aircraft decided to go ahead with the DC-6 model and by 1947 the first DC-6s were flying for United. But the fleet was grounded for several months when it turned out they were prone to catastrophic inflight fires due to a design flaw. Improvements were made and by 1951 the next iteration -- the DC-6B -- was flying domestic routes.

Pan Am took delivery of their first, N6518C christened “Clipper Liberty Bell” in February 1952, just in time to take advantage of the new fare structure that IATA had finally countenanced. For years the round-trip transatlantic air fares had stayed pegged at $711. (At a time when $5,000 was a decent yearly salary!)

Now all the eleven airlines flying the Atlantic would be able to charge low tourist fares, and the race was on.

DC-6B Seating Track (Photo: Aviation Week)

May 1, 1952: The Rush to Fly to Europe

Advance bookings for the new fare were overwhelming. In fact, all the air carriers were racing one another on May 1st, 1952 to be first off the ground with flights to Europe. As it happened, TWA and El Al, the Israeli airline, were both ahead of Pan Am – only just - with their respective Lockheed Constellations leaving the ground at 12:01AM and 12:09 AM respectively.

But Pan American’s first DC-6B was close behind, taking off from New York’s Idlewild Airport for London in the early afternoon, with another DC-6B slated to depart for Paris later that evening. All of these flights were booked solid. The “Connies” maxed out at around 60 passengers, while Pan Am’s Douglas’s carry 82 passengers.

DC-6B: "A New Concept in Transport Aircraft"

DC-6B: "Best of the Breed"

Pan Am’s DC-6B’s were the “best of breed” with upgraded Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines, which were more powerful than previous versions. Gross weight and fuel capacity were also higher. The airline called them “Super 6’s.” There was a complete re-design of the cockpit too, with elaborate upgrades in avionics.

An article in Aviation Week stated:

“For a new concept in transatlantic air travel Pan American World Airways is putting into service a fleet of 39 Douglas DC-6B’s, which in many respects represent a new concept in transport aircraft… Pan American’s Douglas Super DC-6B may be tourist in cabin appointment, but it is super de luxe in cockpit appointment.”

Bottom line: Increased range, higher payloads, better instrumentation. For 1952, Pan Am’s “Super 6’s” were truly “state-of-the-art.”

And Pan Am took another step into the future with an innovation back in the cabin – a change in aircraft accoutrements that would fundamentally affect airline operations in ways both big and small far into the future.

From this day forward, Pan Am’s (and Panagra's) DC-6B’s would have what amounted to modular cabin arrangements, thanks in large part to a new system (patented by Pan Am) of tracks with attachment sockets at 1” increments laid down the length of the passenger cabin, enabling seats and other cabin features to be quickly set up and removed in a flexible way. It allowed the “Super 6’s” to be converted in about 90 minutes from an all-tourist class setup – Pan Am called theirs “Rainbow Service” – to a more exclusive 44-seat or 56-seat luxury configuration.

Pan Am and Panagra DC 6-B Postcard Array (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection)

The New Era of Airline Economics & Travel

So with that May 1, 1952 starting date, the future of airline economics and human travel patterns passed into a new era. The changes ushered in the advent of tourist fares and variable seat pitch. It was arguably the opening of the age of aviation we know today. In fact, worth noting too, the very next day (May 2, 1952) the De Havilland Comet I, the world’s first commercial jet transport left on its inaugural flight from London to Johannesburg – another event marking aviation’s evolution.

Juan Trippe continued to advance his vision for air travel – getting more people flying faster – which culminated 17 years later in the advent of the Boeing 747 and the age of almost universal air travel. And of course, the 747 flew with Pan Am first.